The Discipline of Being

(Honesty, as a practice)

This was a diary entry from last month, written by hand, on paper. At the time, I didn’t write it with the intention of sharing. But lately, I’ve been trying to practice clarity—not just in private, but out in the world. And part of that practice is allowing myself to be seen, even in the quiet, unpolished parts. So I’m sharing this now, not as a finished statement, but as a reflection. A self-portrait in progress.

I appreciate the small luxuries in life: the texture of good linen, the weight of a pen that feels right in the hand, the silence of a well-designed room. If I know something will accompany me daily - a bag, a chair, a phrase - I don’t mind spending more than the ordinary. I see it not as indulgence, but as investment. Not just in durability, but in beauty, in mood, in the quiet rituals that anchor a life. I don’t choose these things to photograph them or to perform aesthetics for others. I choose them because they reflect a way of thinking: that everyday life deserves intention, that utility can have soul, and that beauty, when honest, is a form of care. As Eugeni d’Ors wrote, there is no radical difference between work and play, between necessity and art, between utility and beauty. Some people collect art. I collect usefulness with soul.

I have a distinct taste in clothes and how I wear them. I'm not a big fan of accessorising, even though I appreciate it on others - like my friend Sarah, who has a talent for controlling metals, leather, sequins, and more. She knows how to combine them all in a way that feels intentional rather than chaotic. I admire that, but I only wear a few accessories myself. And when I do, I wear them every day, regardless of what I have on. If there's one thing I do collect, it's sunglasses. I see them as punctuation - subtle yet decisive - in how I present myself. When it comes to personal style, I lean toward solid colours and interesting textures. I like satin for its lightness and flow, paired with heavy cotton that gives it structure. The contrast doesn’t cancel either material - it stabilises the delicacy, and gives softness a frame. I’m drawn to the interplay between masculinity and femininity - not to neutralise one with the other, but to inhabit both. To be sensual and cerebral at once. I can be in a slip dress one day and a hoodie the next - not out of confusion, but intention. I don’t perform femininity for others. I wear softness when I choose, and reject it just as freely. In style, as in life, I aim to be angular, measured, and disciplined - in every sense.

I’m not particularly social, and that’s probably because I have a slightly warped sense of hypocrisy. Keeping people around just for the sake of fun, without even a hint of emotional depth, feels like the worst kind of two-faced behavior. Not towards them, but towards yourself. I don’t walk into conversations with judgment, but the moment I realise the “connection” won’t evolve beyond meaningless entertainment, I’m out. No drama, no farewell tour. Just a quiet exit. I prefer to spend my time on people who can handle both joy and discomfort, who live somewhere between the mundane and the metaphysical, the imaginary and the literary. I’m constantly hungry for thought, for texture, for something that isn’t just noise. If someone’s not adding something to the table - be it emotional depth, curiosity, or even a well-timed silence, I don’t see the point. Friends aren’t background music.

I prefer travelling alone—it makes me feel free and independent. It’s a quiet manifestation of who I am. Choosing to be yourself, regardless of where you are or who you're with, is an act of courage. In the end, solitude shapes character. And to step out of your comfort zone without anyone pushing you is perhaps the bravest act of all. It’s not just a sign of self-respect; it’s a deep acknowledgment of self-worth and self-trust. I am not alone by accident - I am alone by design and in a culture obsessed with noise, my silence becomes political.

I’m deeply drawn to high art: opera, ballet, theatre, and cinema. The multidisciplinary nature of these forms makes me appreciate humanity more than anything else. In moments of disillusionment, it is precisely these mediums that restore my faith: they are testaments to what humans are capable of creating purely for the sake of beauty, meaning, and joy.

You’ll often find me at the opera, seated between sixty-year-olds—the last generation, perhaps, that truly understood the value of devoting time and energy to what we consume. Today, we speak endlessly of sustainability, yet rarely extend the conversation to the sustainability of media or atmosphere. What of the spaces we inhabit for pleasure? The rituals we return to for depth?

Our generation has been conditioned, yes, brainwashed, to think that fast-paced entertainment is inherently fun. But clubs, much like fast fashion, are engineered for rapid production and immediate consumption. They leave no residue, no afterthought. I long for experiences that linger, that require patience, silence, and presence. That’s not nostalgia. It is resistance.

I’m usually very patient with people. I tend to keep things to myself, often choosing silence over an immediate reaction. But—perhaps the worst thing about me—I do hold grudges. I watch closely and take mental notes. I might act as if nothing happened, or mention a discomfort in passing, but if the pattern continues, I eventually open the mental folder I’ve been keeping on that person. I’m a careful observer, and when my patience runs thin, I don’t always let things slide—I remember, and sometimes, I respond with everything I’ve quietly collected, and this is probably the thing I have to change about myself.

I have an unwavering faith. I read and practice religion, and it’s been part of me for as long as I can remember. But the moment I truly understood its weight in my life was when I traveled to South Korea alone for the first time at the age of 14. I was still a child, struggling to adjust to being on my own in a land so far from home. During a moment of distress, I called my mother seeking comfort. She simply said, “I’ve placed you under God’s protection.” And somehow, that calmed me immediately. It struck me deeply—my naive, childlike logic was this: if my mother, who cares more for my safety than I ever could, entrusts God with my well-being, then this God must be worth believing in. Since that moment, my faith has only grown. It has never wavered.

I’ve never had a strong interest in sports. While I enjoy playing tennis or swimming occasionally, they’ve never sparked a real passion in me. That said, I do recognize the immediate and positive impact physical activity can have on mental health, it clears the mind, lifts the mood, and restores a sense of presence. Still, like anything else, when taken to extremes, it starts to unsettle me. Excess—whether in routine, ideology, or lifestyle - tends to disturb rather than inspire. I believe in movement, not performance. And I’d rather walk to clear my head than run to prove a point.

If there’s a through-line in all of this, it’s intention. In what I wear, how I connect, where I go, and what I believe, I try to resist noise and lean toward clarity—even when it’s uncomfortable. My honesty doesn’t always look soft. It sometimes looks like silence, solitude, even distance. But it is, at its core, an act of care. To move through the world awake to texture, to contradiction, to the quiet rituals that shape a self—that is who I am. Not an answer, but a practice.

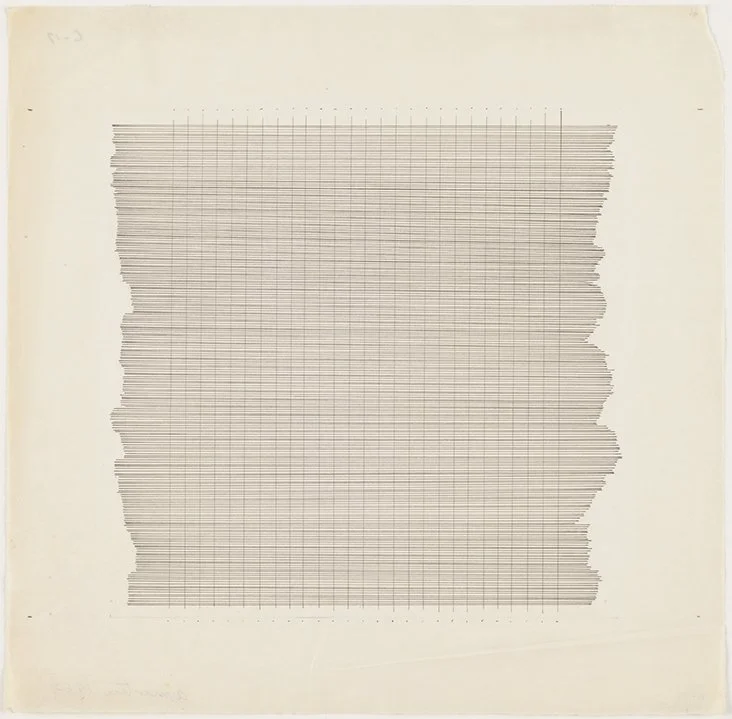

Untitled / Agnes Martin / 1960

Like Agnes Martin’s grids - structured yet unresolved, silent yet full of intent - I’m learning that discipline is not about control, but about making space for meaning to emerge, slowly and without spectacle.