I Belong to the Mountains and He to the Sea

How to stage a tragedy between geology and psychology, with cameo appearances by Magritte, Vesuvio, and one poorly cast Poseidon.

There are two kinds of people: those raised by mountains, and those raised by seas.

The mountain-born learn silence and endurance. They inherit gravity, patience, the conviction that what is built should last. Mountains do not move; they teach permanence. To them, love is a house: solid, protective, rooted in time.

Some are raised by altitude. I was. Mountains train you in solitude, in the discipline of silence. They give you a spine. To grow among them is to learn that stability is not preference but law: either the rock holds, or you fall. From the mountains, you inherit the belief that love is not spectacle.

The sea-born, by contrast, learn improvisation. They inherit charm, irony, the instinct that movement is more alive than stillness. Seas teach motion, evasion, generosity: they give salt, food, passage, story. They carry civilizations in their tide, bearing the weight of histories across distances mountains can never cross. To belong to the sea is to know that restlessness can be a form of courage. Seas do not stay; they recede, they return. They are never the same twice, and there lies their truth.

Where my mountains demanded silence and endurance, his sea gave him transformation. Its constancy lies not in stillness but in rhythm: tide after tide, wave after wave, it returns. He belongs to that rhythm as much as I belong to stone. If I inherited a spine, he inherited a horizon. Where I learned to build shelter, he learned to begin again. His strength is not permanence but motion, not weight but flow and in that fluidity there is a resilience just as profound.

Seas also teach multiplicity. They merge, swell, and mix until no one can tell where one begins and another ends. They thrive in company, in the endless exchange of currents, winds, and shores. To belong to the sea is to belong to the crowd, what the mountain might simply call noise, where intimacy is always shifting and presence is always plural.

Mountains, by contrast, are solitary. They trust other mountains because they recognize their firmness, but they do not mingle. Their distinct solitude is not weakness but clarity. To belong to the mountain is to value the few over the many, the durable over the transient.

And so it is with people. The sea-born are expansive, restless, loud - measured by the chorus of their connections. The mountain-born are contained, loyal, singular. The mountain-born was too vertical for someone who lived horizontally.

When mountain and sea meet, the attraction is not gentle but all consuming. Rock thirsty for water; water rushes toward rock. The sea runs its hands along the mountain’s edges, smoothing them; the mountain steadies the sea’s chaos, giving it a body to embrace and resist. They complete what the other lacks. Their touch is a collision, but also an intimacy, that is violent, tender, impossible to resist. For a moment they seem destined, as if the mountain has waited centuries for the tide, as if the tide has wandered endlessly in search of stone.

Rock erodes; tide withdraws. What begins as devotion becomes abrasion. What once felt like inevitability turns into exhaustion.

Their fights are ancient: the mountain calls the sea irregular; the sea calls the mountain rigid. One seeks clarity—the view from above. The other seeks movement—the shimmer of the crowd. Neither is wrong, but they are not made to match.

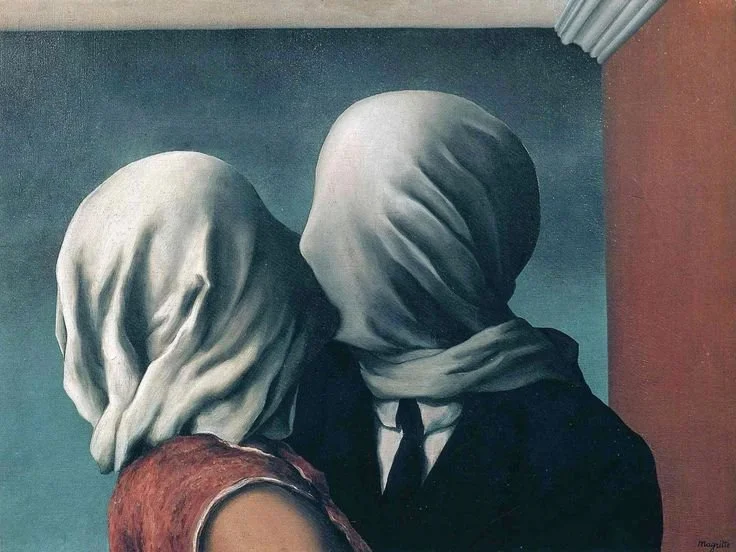

Even strangers can see what lovers will not: both are vast, both are beautiful. But vastness and beauty do not guarantee harmony. It recalls Magritte’s The Lovers II: closeness so absolute it becomes its own barrier, contact that conceals as much as it reveals.

And yet one question lingers: what can a sea and a mountain create?

The answer is the coastline. A place where permanence and motion meet. Coastlines are thresholds, neither land nor water, but something in-between - fertile, magnetic, unforgettable.

That was the possibility: not love denied, but love transformed into form. Together they could have drawn a third space where endurance and change might have coexisted. The chance was not to be each other’s opposite, but to build something larger than both.

The tragedy, then, was not the absence of love - there was love, vast and undeniable. The tragedy was the refusal to let it become a third place of in-between.

Perhaps it is not only people who inherit their landscapes, but love itself that takes on the form of its origin. Geography is not just backdrop but instruction: it teaches us what to value, what to expect, even what to fear. The fight between permanence and change is not only between two lovers but within love itself - between the desire to be held fast and the desire to remain free.

In the end, both are loyal not to each other but to the landscapes that raised them.

This summer Vesuvio suggested a duet to my perspective: stone and sea bound in endless performance, a spectacle lived daily in its shadow and at the mercy of the Gulf. But Vesuvio is not mine. Mine is the Caucasus, where mountains are not theatre but law, where truth is carved, not acted. And yet Naples teaches me another lesson: that even truth, if it wishes to endure, must sometimes step onto the stage.

I belong to the mountains. He belongs to the sea.

What passed between us was not reconciliation, but performance, two landscapes compelled to face each other, knowing the curtain never falls. The audience, of course, left long ago.

The mountain cannot help but watch the sea’s shimmer. The sea cannot help but lift its gaze to the mountain. They remain at a distance, each loyal to its own law.

As if Sisyphus had dated Poseidon.

*Some readers may be tempted to identify the “Sea” with a specific individual. This is an error. The Sea nourishes, carries, and renews. He, by contrast, specialized in doubt and delay. If he appears here at all, it is not as character but as footnote — a methodological inconvenience upgraded, for narrative purposes, into myth. Still, someone had to play Poseidon. His beauty, at least, made the casting believable. This is, somewhat, fiction.

*Scholars, inevitably, have tried to systematize what I reduced to metaphor. Harold Proshansky spoke of “place identity,” the idea that the landscapes we grow up in migrate inward and become part of our psychological structure. Yi-Fu Tuan, more lyrical, wrote of topophilia: a love of place that quietly trains our affections and expectations. Neuroscientists, with less poetry, add that mountains steady the body - lowering cortisol, slowing breath - while coasts quicken it - heightening creativity, loosening mood. In short: biology, psychology, and geography all agree. I only called it love, which was apparently the least rigorous term available.